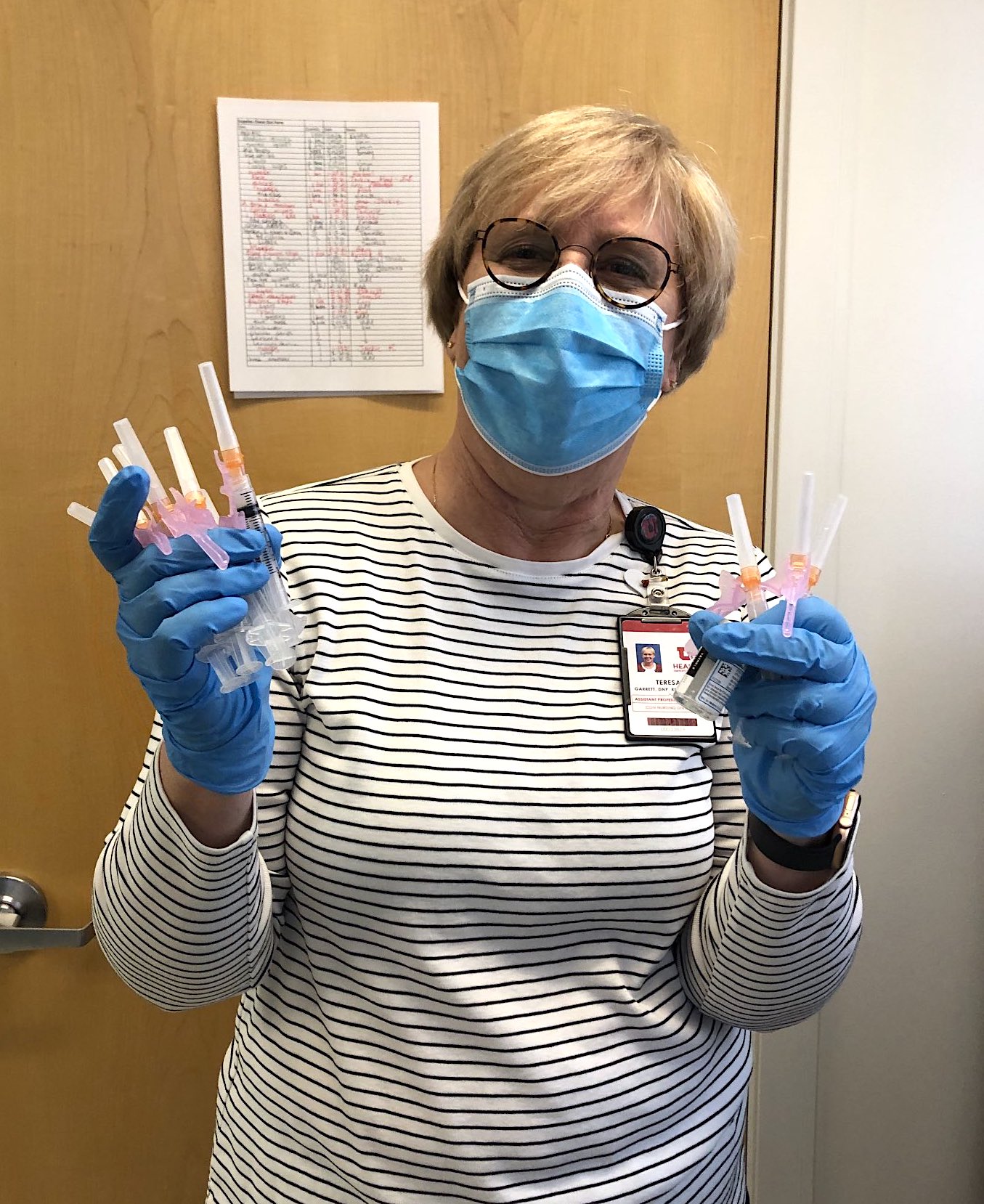

Every time Teresa Garrett, DNP, RN, PHNA-BC, held a syringe during the pandemic, she felt like she was holding gold. Inside the clear, thin tube was a life-saving COVID-19 vaccine. She and her College of Nursing (CON) colleagues knew that vaccination was the only way to stop the wave of sickness and death racing across the world. History told them so.

Garrett, an associate professor, had previously run the Utah Department of Health’s communicable disease bureau during the deadly H1N1 (swine flu) pandemic, which killed about 12,000 Americans in its first year. But COVID-19 was something unique.

“You can’t even really say it was H1N1 on steroids, because there aren’t that many steroids in the world,” she said.

So, Garrett and dozens of other CON faculty, students, and staff joined the army of volunteers across the state striving to get the vaccine in as many arms as fast as possible. As hard and horrible as the pandemic has been, it is a rewarding time to be a nurse. When the novel flu virus H1N1 was detected in the United States in the spring of 2009, health officials were taken by surprise.

“That was scary, because it wasn’t supposed to happen in our hemisphere,” recalled Garrett.

All the modeling had suggested this new kind of flu would start in Asia. Instead, H1N1 appeared in North America—including Utah. But by fall, a vaccine was available and H1N1 soon disappeared from the headlines. With COVID-19, reaching the end of the pandemic has been more difficult. Summit County Health Department, an established faculty practice partner, needed help. So, the CON stepped up. Garrett volunteered to vaccinate and bring students with her.

“Let’s go show them how we do this emergency response,” she remembers thinking.

Garrett and the students stood for hours in the cold in an old movie studio across the street from the health department. Four lanes of cars passed through as vaccine after vaccine went into arms.

“People cried,” Garrett remembered. “People got out of their cars and jumped for joy.”

Students got to see in real time the impact they could make. Some people told Sara Wilson, then in her last semester at the CON, they hadn’t left their house in a year. For her, being a part of the solution to a public health crisis was inspiring. Many of the volunteers in Summit County were retired physicians, nurses, and other specialists with years of medical expertise.

“I felt the camaraderie,” Wilson said. “It was really cool to see people humble themselves for this—to do some common good.”

By summer, as the vaccine became more available, Garrett changed her focus to on-campus vaccine clinics. Those clinics targeted students, encouraging them to “take one for the team,” including athletes and marching band members. Garrett has heard all the concerns: the vaccine causes infertility or heart disease. Some students said it had been approved too fast. She listened and provided the facts. It’s the kind of conversation so many nurses have had since COVID-19 vaccination began. It’s the kind of conversation that continues as vaccination clinics take place at the student union this fall.

“How nurses engage with communities can make a difference in an entire community’s health,” Garrett said.

Nurses weren’t just key to vaccination efforts in Utah, they were also often caring for the sickest COVID-19 patients in the hospital. CON graduate Christy Tran Mulder worked at University of Utah Hospital’s Medical Intensive Care Unit during the first wave of the pandemic, and was sometimes the last person patients saw before they died. She was also the first in the state of Utah to receive the COVID-19 vaccine, something Mulder has described as an honor.

Before the vaccine was available, Emily Royce, a DNP student and registered nurse at the CON and the Urban Indian Center of Salt Lake, was among the many providers caring for COVID-19 patients at home. She helped coordinate testing and distributed thermometers and pulse oximeters. People were sometimes too sick to take public transportation to get medical help. Too sick to walk. Too sick to get groceries or medications. Many of her patients were uninsured and could not afford to take an ambulance. So, Royce and the Urban Indian Center referral specialist found solutions.

“The health disparities became blazingly obvious when COVID-19 hit,” Royce said. “Though not all, many in this population are low income and do not have insurance—most of their work situations do not provide paid compensation for time off.”

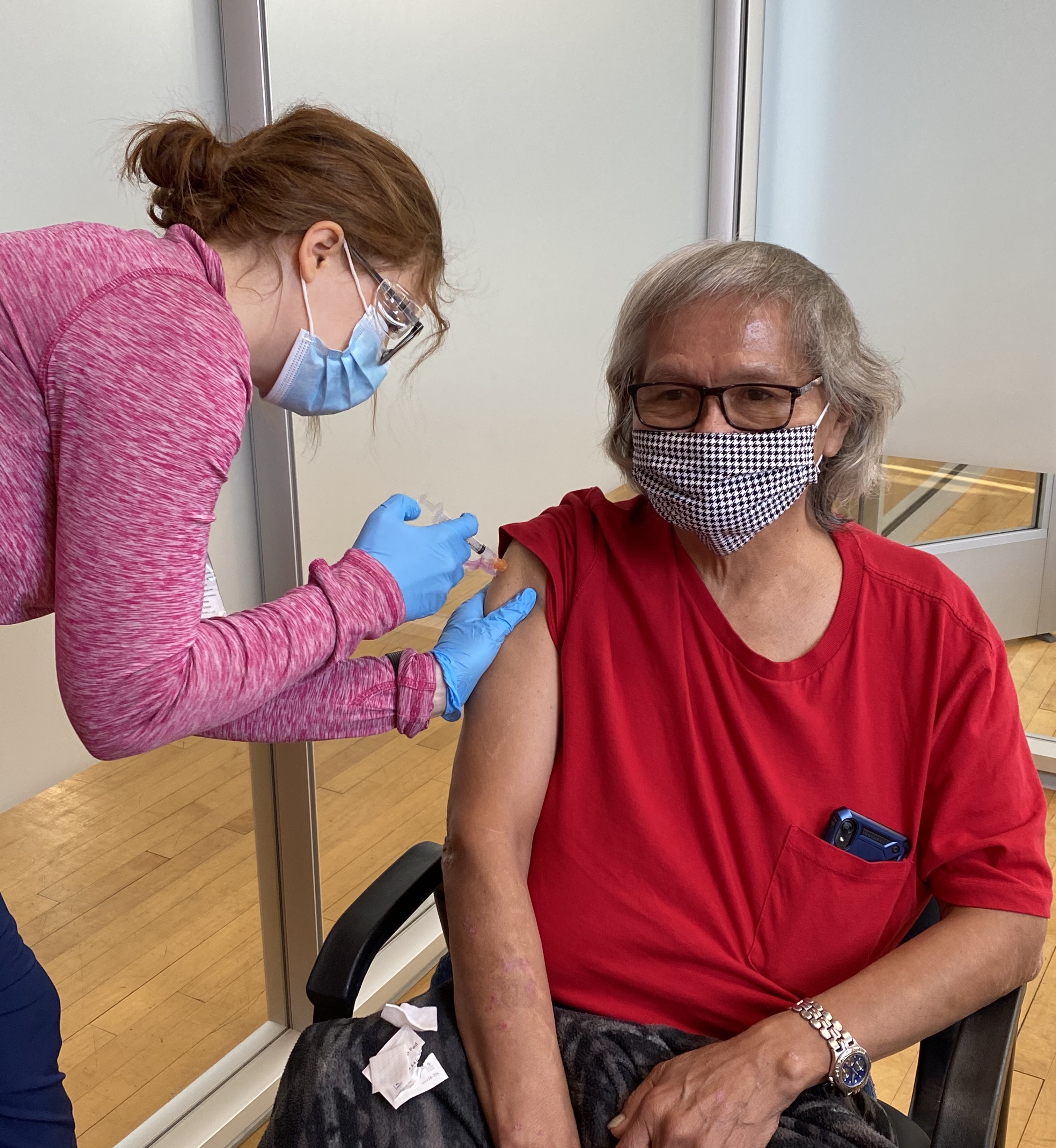

When the vaccine became available, she and the Urban Indian Center medical team worked hard to provide culturally-sensitive care. Native American music played in the background during appointments. After the shots, patients received a bag with everything from hand sanitizer to purifying sage they could burn at home. About once a month in February, March, and April, more than 100 people received vaccinations at Saturday clinics. CON student volunteers were crucial.

“The biggest barrier with giving the vaccine wasn’t the fact that there wasn’t enough vaccine,” Royce said. “It’s that there wasn’t the infrastructure or staff to provide that many vaccines. Students were the way we had the capacity to do that.”

Royce, who is now studying to be a nurse practitioner, taught the students to slow down and spend that extra few minutes talking with patients and relieving their anxiety.

“I think the more transparent you are with the data the more that person is going to trust you,” she said.

Chelsea Harvey was a CON student helping at the Urban Indian Center as she finished her degree. She is part Choctaw, and her grandmother is a patient at the center.

“I got to hear a lot of stories that way and learn more about the Native American side of things and how COVID-19 affected them,” she said.

Giving people their COVID-19 vaccine meant giving people the ability to finally visit their family at reservations. Some people hadn’t been home in a year.

“I didn’t realize there were so many Native Americans in Utah,” she said. “It opened my eyes to how much diversity there is in the valley.”

Thanks to the pandemic, students like Harvey received a temporary registered nurse apprentice license to help alleviate a shortage of nurses. The license enabled nursing students to work in hospitals and, under the supervision of a registered nurse, care for patients at the level of their education while nurses worked with the sickest COVID-19 patients. That was a huge learning opportunity for Harvey who had been forced to do some of her nursing training online and at home during the pandemic.

“My husband was my guinea pig for a lot of things,” she said. “I would tie tourniquets on his arm and try and find veins on him because I didn’t have anyone else to do that with.”

Harvey’s temporary license allowed her to work at the surgical trauma unit at the Intermountain Medical Center in Murray. Working under a licensed nurse’s supervision, she gained experience that would lead to a job in the same unit after earning her bachelor’s degree in nursing. Working at the Urban Indian Center had given her administrative experience, too, as she helped organize the vaccination clinics.

“I learned how much work goes into setting up a vaccine clinic like that and how many people you have to coordinate with to make it run smoothly,” Harvey said. “I also saw how helpful volunteers can be.”

Since the pandemic began, Melanie Wolcott—like so many others—had been working from home. She’d been safely doing her job as the operations manager at BirthCare HealthCare midwifery and women’s health faculty practice managing schedules and budgets, while practitioners were delivering babies in full personal protective equipment. Wolcott, a former labor and delivery nurse with an MBA, felt a little helpless. Too safe in her bubble.

“I wanted to be part of the solution,” she recalled.

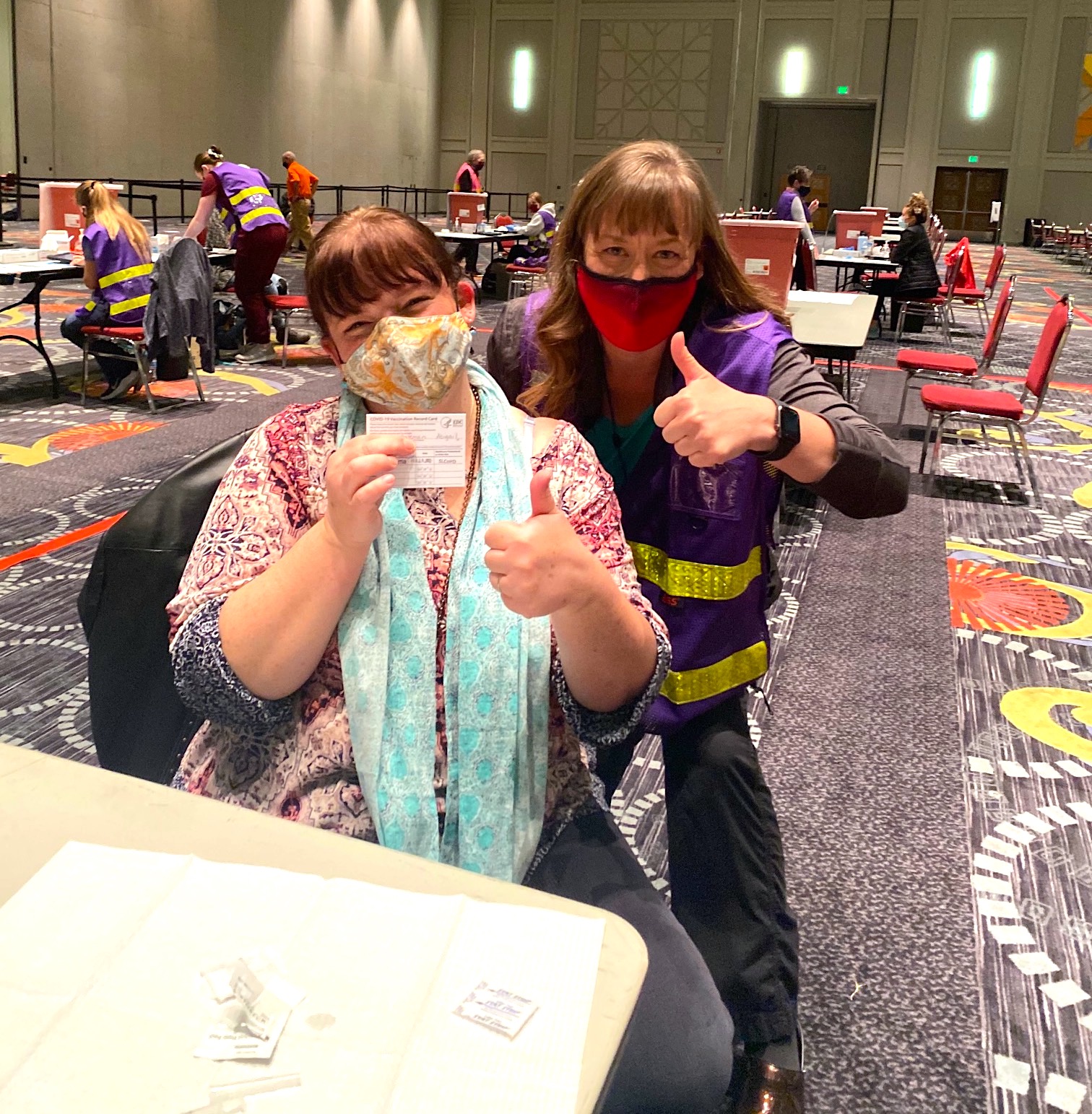

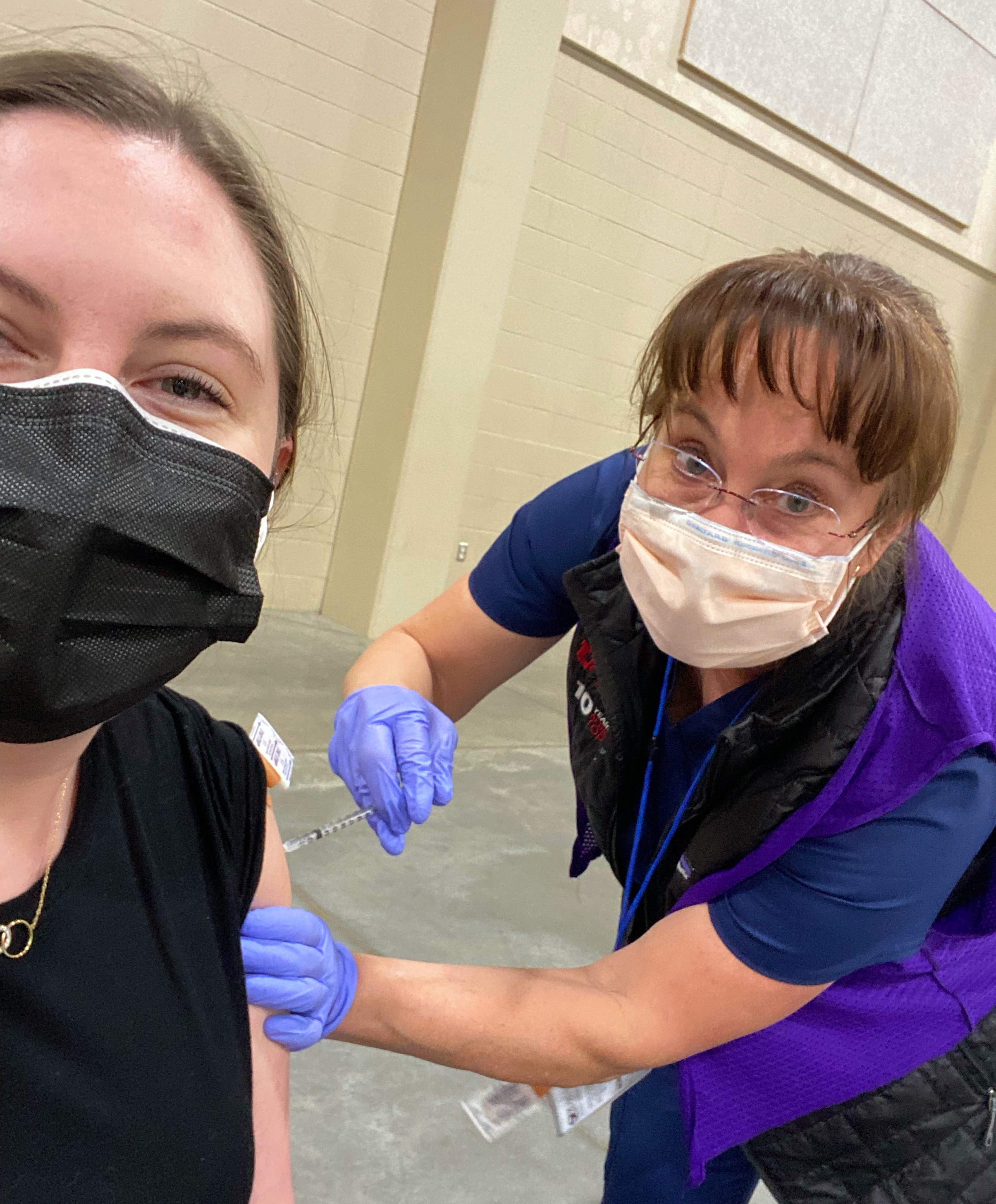

So, when a friend told her about an opportunity to vaccinate the community through the Utah Medical Reserve Corps, she was ready. From January to the end of May, Wolcott was among the hundreds of volunteers—many of them nurses—who vaccinated people in Salt Lake County.

“I think the nurses are what made a difference,” she said. “People came out of the woodwork.”

In the beginning, when demand was high, Wolcott was vaccinating around 100 people per day. Some of them were extremely nervous, and it was Wolcott’s job to explain the vaccine’s potential side effects and help some people overcome a fear of needles. Sometimes she had the opportunity to persuade another family member accompanying the patient to get the shot too. When her best friend said she was coming to the Salt Palace to get vaccinated, Wolcott told her to ask for her table. She knew how much the vaccine meant to her friend, who was a self-employed Reiki practitioner with two young children.

“I got to give her this ability to reconnect with the world again,” Wolcott said.

Her nurse practitioner colleague, Katie Ward, DNP, WHNP, knew all too well how devastating COVID-19 could be. Her 84-year-old father was living in an assisted living facility during the pandemic. He was exposed to COVID-19 walking to and from meals. Diagnosed July 8, 2020, he died three weeks later.

“He had medical problems—something was going to get him eventually—but the hard thing was that we had to let him die alone,” said Ward. “It was such early days and you couldn’t be there.”

The pandemic alone probably would have inspired her to give vaccinations. After her father’s death, she was on a mission.

“People should not lose their parents or loved ones to a vaccine-preventable illness,” Ward said. Her daughter, who does not have a medical background, volunteered her computer skills. Just like in Summit County, people of all backgrounds came together to help Salt Lake County’s community. Retired midwives, physicians, firefighters, and nursing students.

“It was some of the most fun I’ve had professionally in a long time—being part of a team,” Ward said. “You kind of get why people kept coming back for more.”

Ward, an associate professor at the CON, taught graduate students who, like so many others, struggled to do coursework from home during the pandemic. In many cases, their kids were attending school in the living room or kitchen with them. Some of the graduate students were working extra shifts. But, all of a sudden, their coursework seemed much more relevant.

“The pandemic really brought to life a lot of things we talk about in theory—how the public health system works or does not work, and the importance of understanding evidence,” Ward said. “There’s been a lot of science really brought to life.”

Back in January, there were ten lanes of vaccination tents with cars queued up at the Maverik Center. Volunteers like her were injecting vaccines as fast as they could.

“It was kind of a marvel they pulled all this together,” she said.

When Ward returned to get a pre-travel COVID-19 test this summer, she was heartbroken that no one was there to get a COVID-19 vaccine. All of the people were there to get tested as the Delta variant surged. Many Salt Lake County adults remain unvaccinated. Some health clinics, like hers, now house the COVID-19 vaccine on-site giving providers the chance to vaccinate someone during a regular appointment. Ward recently cared for an older, unvaccinated patient with significant medical issues. Her husband had accompanied her to the clinic.

“I think she wanted the vaccine—he asked me what I thought,” Ward said. “I told them about all the benefits of being vaccinated.”

She told them getting COVID-19 was way worse than whatever they were hearing about the vaccine. Getting “natural immunity” meant risking their lives to the infection first. The couple agreed to receive the shot, and Ward ran out of the room to make arrangements. She hugged her medical assistant with happiness. It was the first time she’d been able to convince a patient in the clinic to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. She thinks having it immediately available is a game changer.

“I’ve seen a lot of patients who’ve told me they don’t want to be vaccinated,” she said. “I’ve felt like nothing I say makes a difference.”

She often does tell people about her father, because she’s found that many patients don’t know anyone who died or even went to the hospital.

“In their mind, it’s a mild thing people recover from—and it’s not a big deal,” Ward said.

So, she will keep sharing her story. One patient at a time. Because COVID-19 is far from over, and every vaccine matters.