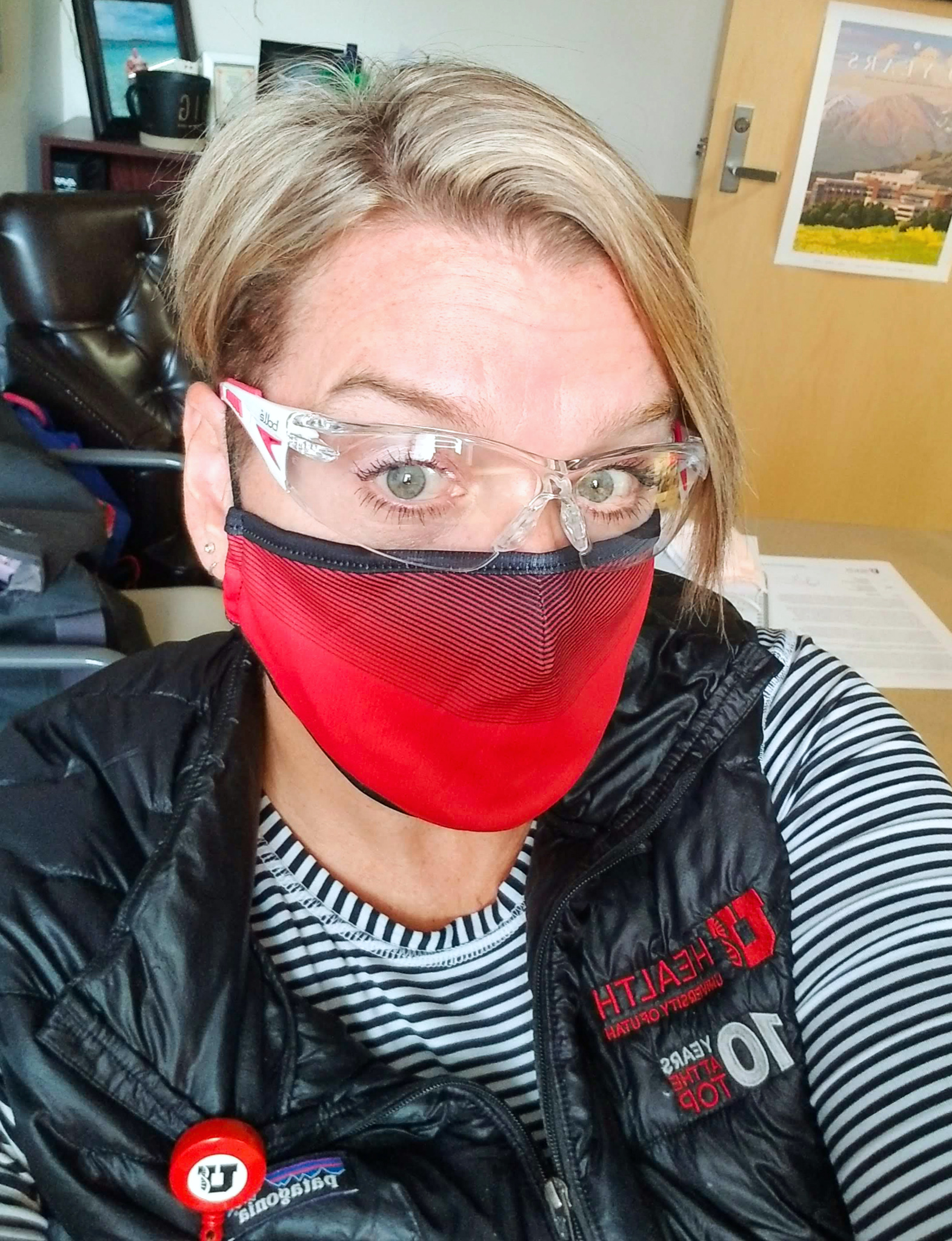

On the morning of March 18, 2020, Melinda Patterson (below), DNP ’19, RN, OCN, NE-BC, and nurse manager, pulled her team together in the University of Utah Hospital’s Emergency Department.

“It was challenging for me to keep a steady, professional approach, when part of me wanted to run and hide,” she recalls. “But my bigger desire was being present, and standing alongside my staff, no matter how I felt on the inside. I knew I needed to show up for my team because they were showing up for me.”

And show up they did. Nurses not scheduled to work that day rushed to the emergency department without being asked or called in. They wanted to help care for patients, provide extra moral support, and relieve team members who needed a break or wanted to check in at home.

“We became nurses because we care,” she explains. “The crises we’ve experienced recently are what nurses are trained for—this is our time to help people.”

Patterson praises administration for helping her and the emergency department adapt and respond quickly. “Our university and hospital administration were incredibly supportive. They were present, communicative, and transparent, which helped create a commu- nity of nimbleness,” says Patterson. “Everyone at the hospital from the top down—facilities staff, parking/valet, each department—we all truly worked together to meet the needs of our patients and put safety first.”

Patterson’s leadership team within the emergency department made sure to be physically present twice a day during shift changes to update staff, but also to show solidarity with those implementing each new practice, policy, and procedure. The group made regular rounds to each respiratory tent to provide updates, show staff how to use personal protective equipment (PPE), and address any questions or concerns.

“We wanted everyone to hear the same things from us, personally,” explains Patterson. “We made sure we were on the ground with staff—morning and night, even on weekends—not just behind literal and figurative curtains.”

Julie King (above), MSN ‘88, CNM, is also part of University of Utah Health’s provider network through Birthcare Healthcare at the University Hospital and affiliated clinics. As the pandemic ramped up in early March, King and her team of certified nurse-midwives and Nurse Practitioners took immediate action to protect themselves and their vulnerable patients. Providers and staff implemented face masks, wore scrubs instead of office apparel, and made necessary distancing accommodations in clinic and waiting areas.

Each midwife and nurse practitioner’s schedule was evaluated to determine which of their patients needed to be seen in person, through virtual visits with telehealth, or if their appointment could be postponed. Providers began two week rotations of in-clinic practice before rotating to virtual visits, charting, and other work from home. This solution allowed each “pod” to maximize personal health and participate in precautionary self-quarantine during their two weeks away from the hospital. It also allowed extra room for coverage in case a provider was exposed, or otherwise felt unwell.

Hospital practices also changed significantly. Only the mother and a single support partner are allowed in the room during childbirth. If a patient is positive for COVID-19, only one nurse is allowed inside the room with the midwife. A second nurse attends outside the room with a sterile cart of supplies, only entering when absolutely necessary. Other amenities such as water birth, or laboring in a tub were initially removed or limited, but are now accepted as long as the mother is healthy. Universal testing for COVID-19 is mandatory for new mothers preparing to enter the hospital for a delivery.

“Patients were concerned about hospitals having availability for them when they went into labor, and it led to some great conversations about options,” says King. “Some women choose to deliver out of the hospital at home, or in a birth center. After birth, we know we can now more easily meet their needs using telehealth services.”

Amy Hartman (above), BSN ‘04, RN, Founder and CEO of Solstice Home Health, Hospice and Palliative Care in Salt Lake City, says COVID-19 has profoundly impacted the way her nursing team interacts with patients, but agrees it has given her company a chance to improve and adapt to changing care needs for homebound patients and those near end of life.

“When COVID-19 became an issue in March, we prepared a temporary crisis response, but we quickly came to understand what something like this would mean for us and our patients,” says Hartman. “Our focus changed from short-term management to providing advanced care for the future.”

Hartman and her team asked difficult questions and brainstormed solutions to issues like patient isolation, caregiver/grief support, end of life care, and how to uphold relationships with long term care partners. Nurses acted quickly to meet rapidly changing needs and safety guidelines. In one situation, nurses who usually traveled among multiple clients and locations were assigned to one care facility at a time, limiting both personal exposure and cross-contamination between patients.

“Our entire team stepped up at a difficult time and responded to help our community,” says Hartman. “It’s inspiring to see how our nurses have helped patients and their families.”

Some changes stemming from each nurse’s COVID-19 response may stay in place for the long haul. Many nursing professionals believe increased awareness of infection control will pervade long into the future, perhaps shaping better safety management practices across the health care community.

Nurses on Hartman’s team now set up no-contact delivery of medication, and supplies for home-bound patients. They’ve maximized call technology, using platforms like Zoom or Facetime, to support team communication and provide interactions between patients and families during isolation. These tools allow nurses to customize patient experiences with better access to care through music, social, and spiritual counselling.

Both King and Hartman incorporated and ex- panded telemedicine and communication services into their practice. Virtual visits provide a large convenience factor for providers, as well as patients and caregivers, who can then take less time away from work or home, and have less worry about transferring themselves or a loved one to a health care facility.

In hospitals and emergency departments, Patterson points to improved screening and maintaining patient separation as tools that will continue to keep patients and staff healthy. She also believes the level of communication developed in response to rapidly changing protocol will remain high. As new processes are implemented, information is shared in as many ways as possible.

“We sometimes joke that we’ve accomplished things in five months that would normally take five years,” says Patterson. “I’m grateful our organization moved quickly. We’ve learned things on the go that will help us respond better, or anticipate needs in the future. I’ve been a nurse for nearly 20 years, and now my career is in the middle of history.”

Another new standard in health care practice is the elevated use of protective gear and decontamination procedures many nurses undergo as they transition from work to home. The omnipresent mask, goggles, and face shield serve as a constant reminder for King and others like her that they could bring home a virus or spread COVID-19 to another patient. “The gear makes it personal,” comments King. “You remember the reason you’re wearing it—it makes it real.”

Nurses often take extreme, but necessary, measures to ensure they limit the possibility of contamination. Patterson recites an exhaus- tive routine after returning home from a shift: she removes shoes outside, isolates whatever clothing or scrubs she’s worn, and races to the shower—all before coming into any contact with her family.

“We essentially add those 20 minutes (of decontamination) to a commute,” adds King. “I’m not really home until I’m clean enough to come into contact with my family.”

Patterson devised a readiness plan with her spouse to make sure she had a place at home where she could stay if she contracted COVID-19. At the onset of the virus, Patterson avoided almost all physical touch with her daughters and husband. Patterson’s aging father also lives in the home. She hasn’t hugged him since March.

Personal cost aside, nurses continue to step up their standard of care and meet patient needs. This includes setting up virtual visits for health care providers, facilitating these interactions for both patients and providers, managing additional safety protocol for staff and patients, as well as thinking outside the box to meet patient needs.

Patterson is bolstered by the resilience of her own team, as she observes nurses going beyond professional requirements to comfort patients, providing care in ways often reserved for family members. Due to limited numbers of visitors allowed to be with patients, Patterson’s team sets up video calls for patients to visit with extended family, take selfies, and spend extra time talking or joking with patients.

“Everyone is doing their job and keeping a good sense of humor, which is important,” Patterson continues. “As nurses, we’re sharing a broader sense of community.”

For Hartman, King, and Patterson, the feeling of community started with their education at the College of Nursing (CON). All emphasized that the College prepared them to respond well in times of crises.

Hartman credits her training at CON with teaching her how to critically examine and think through different scenarios to quickly make the best call—things now helping keep her business operational and safe for those she serves. “Those skills are my greatest asset as a nurse and business owner,” Hartman says. “As nurses, we think through worst-case scenarios and problem solve all the time. We’ve had practice managing emergencies our entire careers. We’re taught to lead by example, work as a team with other nurses, and act as advocates for our patients.”

Many faculty members at CON are nurses with past or active careers in the field, which bridges the gap between education and experience. Educators build wellness and awareness into their curriculum, and direct those in need to a variety of resources including the school’s Resilience and Wellness Centers, the Employee Assistance Program, and various extracurricular activities such as mindfulness breaks or breath work to help control stress. The CON works with each cohort of students to implement specific peer support groups so students always have someone to reach out to or text if things get tough.

“The College of Nursing embraces a culture of wellness, while also acknowledging it’s ok NOT to be ok sometimes,” says Patterson. “The school tries to be a safe, healing place for everyone so we can care for each other, ourselves, and ultimately our patients.”

“I got an excellent education from CON, and it’s why I came back to the University of Utah to practice,” explains King. “The college is so well-integrated with the University of Utah Hospital to provide the best hands-on training, and our practices are based on the latest advances in care. The evidence-based training we receive allows us to respond and implement procedures right away.”

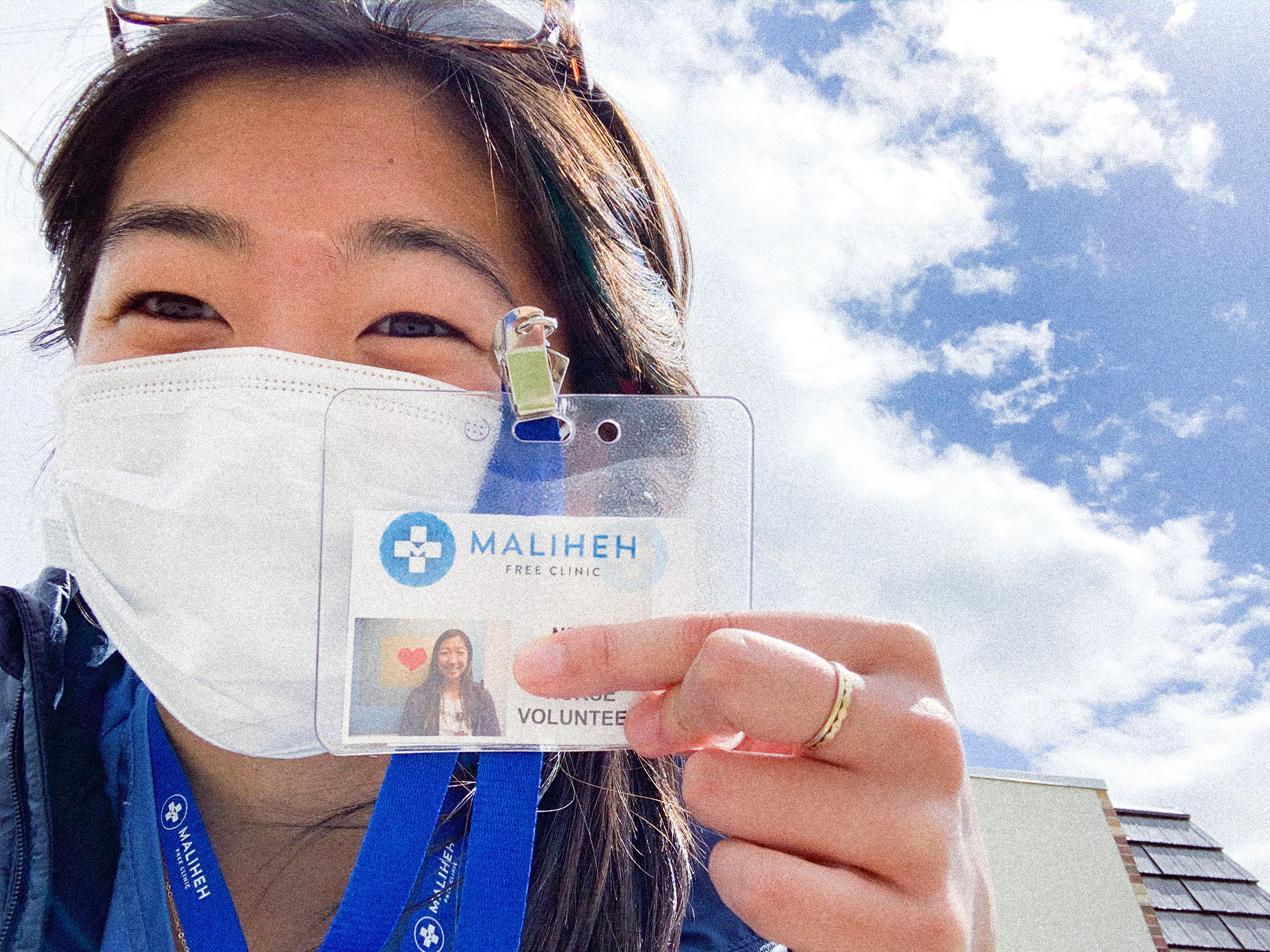

Nene Maruta (above), BSN ’20, one of the CON’s most recent graduates, is preparing to enter a highly sought-after residency program at the Mayo Clinic this fall. Maruta says COVID-19 made her final year especially challenging as she navigated online courses, reduced clinical hours, and the complexities of residency interviews.

“Finishing nursing school in a pandemic was one of the most frustrating experiences ever,” she laughs. “Like a lot of nurses, I’m more tactile and conversation oriented, so it was harder to enjoy things moving online. I had to acknowledge the frustration and find the best way to move on.”

Maruta and the rest of her cohort expressed sadness over relinquishing field experience as clinical and training hours were reduced to accommodate health precautions, but credits the school with moving quickly to make sure education was adjusted for each group of students.

Despite this year’s discouragement, Maruta feels more energized than ever to take on a nursing career. “We got into nursing because we want to serve, and take care of those who are sick,” Maruta says. “The shared feeling is that we want to be out there and experience the true value of health care. Health care can feel like a privilege more than a right, and I want to combat that, especially now.”

“I’ve felt angry at the virus for taking part of our education, but it’s made me eager to get out and help,” she continues. “I’ve had the opportunity to provide education and answer questions for friends and family. Increased empathy for others through shared experiences. This is what nursing is all about.”